I earmarked this article https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5017 a year ago as an important analytical piece on using a systematic approach to improve care. It spoke to me about personalising care, and systematising how that is done, and about reducing wasteful variation by targeting resources on care that met patients needs. It also spoke about communication, and assessing patient need based on conversations.

The article tackled something else too; semantics. The authors debated the meaning of the term ‘best supportive care’, and whether it is the same as palliative care. ‘Best supportive care’ is a phrase that comes back to us from MDT meetings, where patient treatment options are systematically reviewed and agreed by experts. Patients who are too unwell, or who reject, active treatment of their cancer are allocated to ‘best supportive care’. What that means, who provides it, and whether it is different to palliative care is all a moot point.

In the responses to the paper, the debate continues; will this term become a euphemism for palliative care? And who decides what best supportive care entails, and who is responsible for delivering it?

Looking at the experience of patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer in Fife, it was clear that something was not right. Patients and those around them described uncertainty about who was overseeing their care. There was a lot of variation in actual care and support provided, but this did not equate to need, and was a product of a lack of a systematic approach.

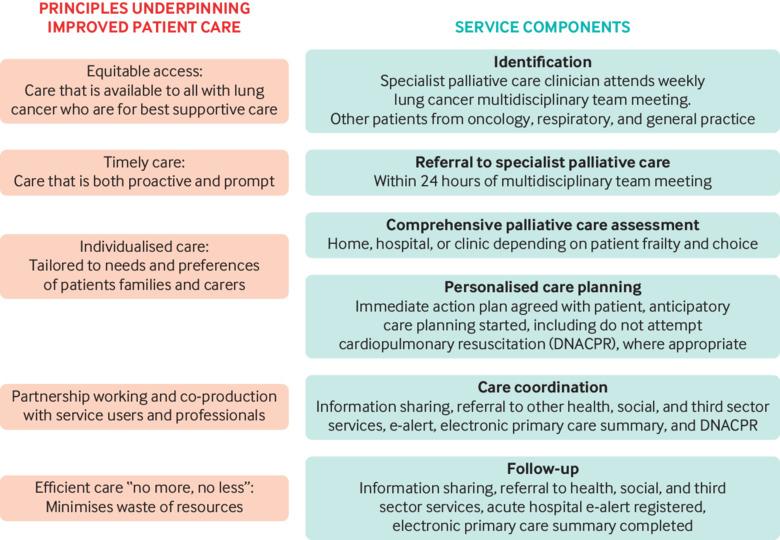

The system that the team in Fife devised based itself on realistic medicine principals.

While this plan looks only at the care of patients with lung cancer, it could be a blueprint for the development of similar services. For example, on our small patch of the Hebrides, it would be sensible to use this approach for all patients requiring best supportive care.

The plan starts with a comprehensive, patient-centred assessment of need, led by a senior clinician. In Fife, where the team started with lung cancer patients, the assessment was a senior palliative medicine clinician. In the Hebrides, we would have to cut our cloth accordingly, and this may be a cancer care lead GP, or a MacMillan nurse. Our own experience is that patients like to know which GP and MacMillan nurse is overseeing their care. One key feature of the assessment is that it is about exploring understanding, discussing implications, and evolving the conversation towards care planning and support.

The second key step in Fife was communicating with all of the professionals identified in the initial plan, including setting up a Key Information Summary. Communication is so easy to do badly, and makes such a huge difference when done well.

My own experience is that this is an iterative process, and the cycle could easily be repeated as circumstances change. The experience in Fife was that over the first three years of the project, systematic change spread through palliative care service delivery.

A treatment that lacks evidence, does not have a realistic outcome or benefit, or that is not really useful for the patient, is a resource wasted. Saving the patient from unnecessary treatment also saves resources, which can then be redirected into support. The health economics of this change in focus is mentioned, but not described; the authors mention this as a barrier to achieving change, as the savings and investments are across organisations and budgets.

Their argument is that delivering what really matters to patients enables effective clinical care without overuse of resources. We know that sounds right, even if the healthcare economics are hard to pin down.