I attended the recent RCGP meeting that debated the role of General Practice in addressing the Health Inequalities that afflict many communities in modern Scotland. The papers presented were the product of years of reflection, effort and involvement. The debate was free-ranging and well-informed, there were many ideas to assimilate, and many questions that arose.

This is my personal reflection on the day (and yes, this is going into my appraisal portfolio).

What is deprivation? The term socio-economic deprivation refers to the lack of material benefits considered to be basic necessities in a society.

Deprivation, poverty and adverse health outcomes: The meeting discussed various aspects of deprivation, poverty and adverse health outcomes, but the relationship between the three is complex. For example, rural fuel poverty creates very real suffering, but the communities that it affects do not always suffer from lack of a supportive society, which mitigates this. Rural life expectancy is longer than might be anticipated given the compounding effects of isolation and financial difficulty, but dispersed deprivation is a lonely place, and is becoming more prevalent. Pocket deprivation is evident, but it is not so easy to compare the adverse outcomes from pocket deprivation with blanket deprivation. The three are linked, but the outcomes are not predictable.

Austerity has had a significant impact, through the exacerbation of poverty, and the entrenchment of deprivation. It is therefore no surprise that the policy of austerity has been associated with worsening of health outcomes, especially in areas of blanket deprivation. Austerity has affected individuals in our communities through reducing their economic freedom, and it has also affected those who wish to mitigate and counter deprivation by reducing their resources and effectiveness.

Core General Practice: My experience of exchanging roles with an urban practice taught me that the core strengths of General Practice lie with Barbara Starfield’s ‘4Cs’; first Contact accessibility, Coordination, Comprehensiveness, and Continuity . They are as effective in rural and urban settings, in areas of affluence and of deprivation.

An effective partner in all primary care settings has a deep connectedness with their community, a commitment to co-ordination of the care for their population. This long-term relationship with a community and the individuals who reside within it brings benefit to everyone. This is as true of rural as it is of urban general practice. The hardest part of participating in my exchange was the feeling of being disconnected with the follow up of new clinical relationships, the inability to sustain the contact into continuity, or to affect the comprehensive nature of care, or its co-ordination.

A principal GP has ownership of the problems and solutions for the delivery of health care in their practice.

I also learned much about how the exchange practice has addressed their challenges of providing effective health care in their setting. Meeting their link worker was inspiring and I have made some lasting friendships.

A forest or a bonsai collection?

We talked about how expansion of the multidisciplinary team is part of the effort to support General Practitioners, to free their time to lead primary care. The models that the envisioned MDT is based on include projects like Govan SHIP. The link workers, pharmacy support, physio and CPN teams, treatment room teams and vaccination programs need accommodation, and the sense of membership of the team.

Underfunding these MDTs, failing to provide adequate accommodation, or resource for the IT, is a substantial risk. A tree in a small pot, with only just enough water each day, and with growth pruned to stay within the resource, is a small and contorted tree. If we want General Practice to provide a forest canopy of health resource across Scotland, we need to nurture it with strong roots, and the space and resources to grow.

Investment in the General Practice of the future must address accommodation as well as teams.

Moving forward: Tackling the hard problems

The Deep End project has shown us that tackling the hard problems, or even just one hard problem, provides benefit for all, the evidence shines a light on how we work. There is great potential for spread of good practice through the worked example. This is a model for moving forward; resourcing the right people, and giving them appropriate goals. More funding for General Practice is not just about fair pay, it is about building resource, supporting and inspiring GPs to use that resource to tackle their own hard problems.

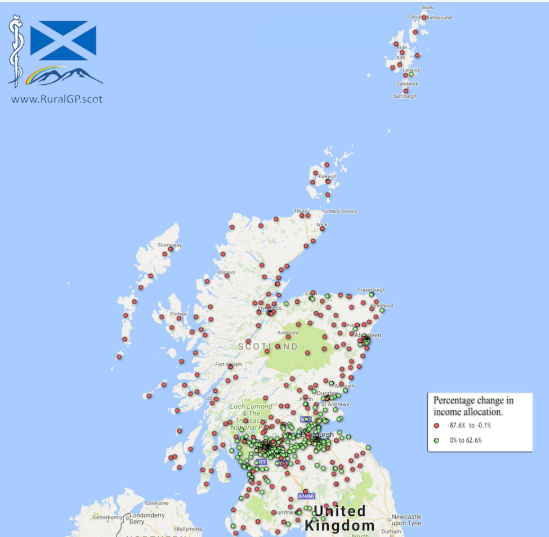

We also need data, and we need to ask for the data that describes where we are, and can be used to show change. An important part of the way forward is to ask for information and data, and to share that unflinchingly, to create a landscape of information that can show where we have been, and where we should direct our attentions.

Heroes and pedestals: As I sat in our meeting, I heard many eminent people speak honestly about their aspirations for what General Practice can deliver. I had arrived feeling an imposter, I had not produced a paper, or had time to assimilate the many papers that arrived in the few days before the meeting. I have not been elected to a high office, nor am I an academic GP. It then struck be that if we put our heroes on too high a pedestal, they become remote, and we fail to see that we are like them, and lose the courage to believe in our own contributions. I had been invited for a reason, because I have something to add to the conversation.

Being a GP partner fulfils my idea of myself as a clinician, and I would advocate that demonstrating and describing this fulfilment should be a beacon to the young GPs who will become the leaders in our profession in the future. We must continue the work of identifying and describing the methods whereby future General Practice can bring the best healthcare to all of Scotland’s people. We must also show that what we do is achievable and applicable everywhere. We must harness the ambitions of GPs to drive forward our agenda, the high energy of collective ambition.