I am Dr Kate Dawson, one of the GPs at Benbecula Medical Practice in the Outer Hebrides. I have been working here since 1990, with three short breaks to complete some training, and when I had my babies, who are now grown up. We are lucky to live in a beautiful and precious place, which is generally safe and kind. I love gardening, knitting, and observing our wildlife when I am out walking.

Our islands, though, are very vulnerable to change. Global warming is bringing unpredictable weather, and rising sea levels will change our coastlines. It is getting more difficult to recruit staff, and travel links are not as good as they were a few years ago.

In the face of this, I have been considering the sustainability of the healthcare system that I am part of, and how we can make positive changes that will help our patients achieve better health, and at the same time, reducing our impact on resources. I dived in to think about this in more detail in the last year and found more than I thought possible.

What does sustainability and the environment mean in terms of health care? Here are some of the ideas that may affect patients directly. Some items will not surprise you, others might.

- Patient transport. This includes trying to use active transport such as walking and cycling, using electric bikes and electric cars. This can be hard when distances are long, and our roads are narrow. However, this also includes trying to avoid travel to appointments when a phone call or video link would be as effective.

- Waste management: Unused medication should be returned to the surgery for safe disposal, so it does not cause environmental contamination. You can also help by only ordering what you need when ordering repeat prescriptions. Empty inhalers and insulin pens should be returned to the surgery. Incinerating empty inhalers causes less damage than the gas in the inhaler being left in the environment.

- Better prescribing: As an example, inhalers have a particularly detrimental effect on the environment. One MDI inhaler is as damaging as a drive to Inverness, whereas one breath-activated inhaler is equivalent of a drive between Griminish and Balivanich. Unnecessary and ineffective medication is a waste too. Don’t cut down on your inhalers, get advice about managing your asthma more effectively, use your preventer more, and ask to try a switch to breath activated inhalers.

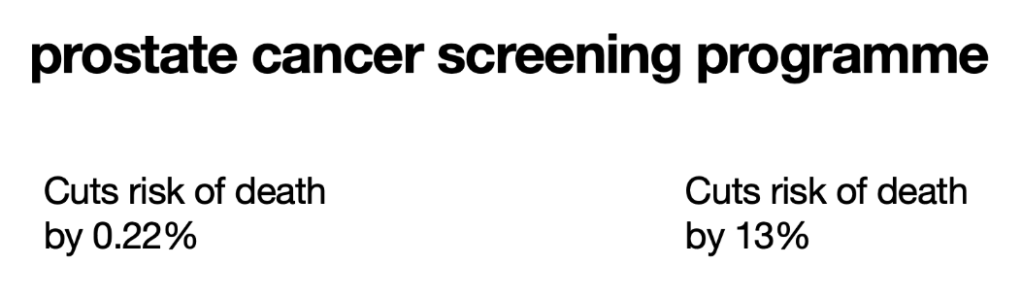

- Better decisions: Better discussions about treatment and referral help patients and doctors make better decisions. If you are referred for a treatment that you Don’t really want, or which may not benefit you much, then it is far better to discuss this before the travel, prescribing, tests and worry begin. It begins with talking frankly to your GP about the benefits, risks, and alternatives to the proposed treatment, and to ask what would happen if you did not seek treatment. Take someone with you if you need support with these discussions.

- Good health is more than medication: Our current medical model from the twentieth century has been about patients coming to the doctors, their ailments quickly assessed, and a treatment or procedure prescribed. With authoritarian health care, the patient can become a passive recipient of medical care, and every ailment is met with a treatment or a procedure. There may be another healthier, less wasteful, more sustainable way.

Imagine this; you can improve your appearance, reduce your need for medication, your reliance on health care, improve your energy levels and joy in life, the benefits will last for years, and the cost is minimal. I am really excited with the possibilities. What is the secret? What if everyone could do this, it would reduce reliance on health care resources, and we would live to enjoy health into our retirement. I am talking about improving health by improving fitness.

As an example, the most cost-effective treatments for Chronic Airways Disease (COPD) are physical activity, smoking cessation, and flu immunisation. These three things are associated with better outcomes than any inhaler or medication.

I am using the word ‘fitness’ for a good reason, as it covers lots of concepts. It does not focus specifically on weight, or exercise, or smoking, or alcohol. It just focuses on being healthier. Where should you start? The beginning is to think about what you want to improve, to imagine what your goal is, what is driving you to consider making a change. Give yourself permission to write down or say aloud what you want to change, what could be better. Perhaps you want to be less short of breath, or your knees to hurt less, or to feel less lonely. Your goal will inspire you to keep trying. You could list all the things you might want to change and work out what you need to do for each thing.

Don’t try to change everything all at once. It is better to focus on one easy thing at a time and make it about fitness and fun. This year, for example, I plan to go for a walk at least once a week. If I miss a week, I have given myself permission to try again the next week, and not to give up when I fail. Last year, we started using smaller plates to reduce our portion sizes without cutting out our favourite foods. You Don’t need Lycra, or to run, or to go on an extreme diet, just find one thing that you can do, that you can enjoy, and make that into a habit that you can sustain.

Who are your allies? Have you got a trusted friend to talk to? A professional such as a physiotherapist, counsellor, nurse, or doctor could listen and support you, if you asked for this; the most important thing is to find someone who can listen to you. They may help you work out what you might be able to do next, to identify one thing that you can do easily, and to support you too.

Your one change may bring more benefits than you think. Going for a short walk will improve your fitness, and it will also raise your mood, reduce isolation, and ease joint pain. Meeting up with someone else for an activity such as knitting or singing will improve your mental agility, and will also reduce isolation, low mood, and loneliness.

As you start to improve your health, you may inspire others. We could have a new normal, in which we support each other to take steps to improve our health through simple changes to our lifestyles, reducing our reliance on medication and leading more fulfilling and joyful lives. We can help the environment and the NHS stay sustainable by creating our own better health.

For ideas, why not listen to Michael Mosley’s podcast ‘just one thing’ on BBC sounds.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p09by3yy/episodes/downloads