I’ve been visiting family and friends, and as often happens, we compare medical notes. How easy is it to visit your GP? Who has the worst osteoarthritis? What medication have each of us been prescribed for high blood pressure? All of our social networks and norms are in play. Our family has a tendency to regard illness as a weakness,, and any visit to the GP involves careful callibration against the family norms.

One sister prefers to seek alternative solutions, changing her diet, drinking apple cider vinegar for her joints, and doing yoga. Another does not vist her GP or look for health issues on the internet, but pursues a very healthy lifestyle. My brother has sought private advice, my mother has checked with multiple medically-qualified relatives and friends. My dear dead dad used to boast about the top specialists he used to see, but would check in with me to see if I had heard of them, for validation.

Ever since I started medical school, I have been a sounding board for all sorts of friends and relatives, even before I had started my clinical years. In recent years, this has increased in frequency, and I have been wondering about this. Do people trust their GP and other qualified health professionals less? We can check everything on the internet, but sometimes that information is unreliable.

There are a number of factors in play. First of all, access to the internet has been growing over the last twenty five years. Artificial intelligence means that search engines can prioritise and summarise information quickly, no appointment required, any time and anywhere. Official sources of information such as NHSinform and patient.info can be a boon to health professionals, who can signpost to them for a modern take on the information leaflets we used to stock, and more likely to be up-to-date. Specialist websites provide a sense of community and support for conditions such as diabetes or muscular dystrophy.

Reliance on digital support for healthcare marginalises some groups. Statistically, older women are the least likely to be IT literate or to trust digital solutions, but low income, deprivation, language and cultural barriers are all in play. The affluent, urban, busy professional has become the target audience.

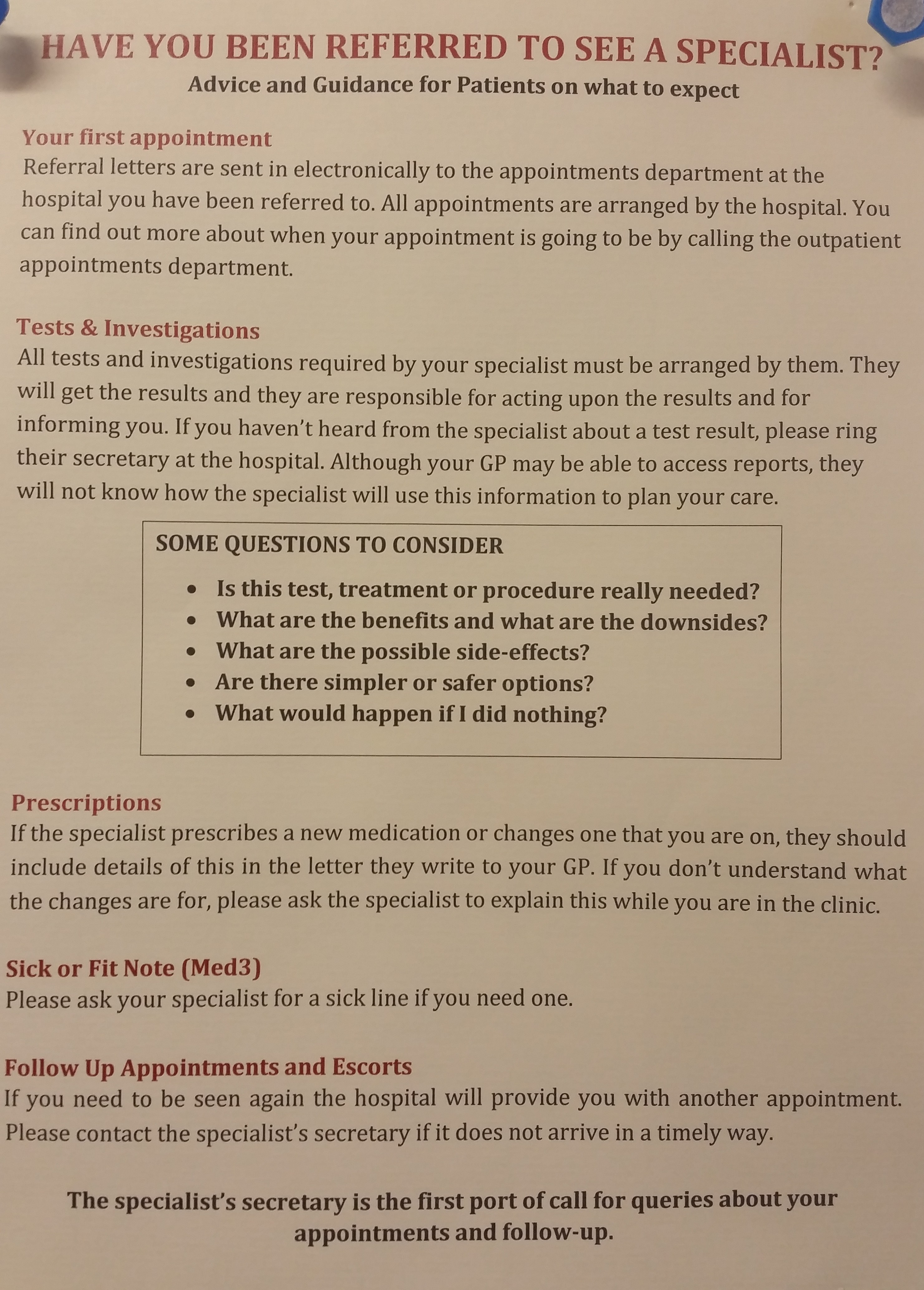

As a health professional, when I speak to a patient with high levels of understanding of their condition, and good health literacy, this is both a blessing and a stress. The fully engaged patient can participate in discussions about various health care options, can evaluate information, and challenge my own assumptions and knowledge base. This same group of patients may defer decisions so that they can evaluate and research their health questions further. It can be time consuming and intense, and of great value to the patient.

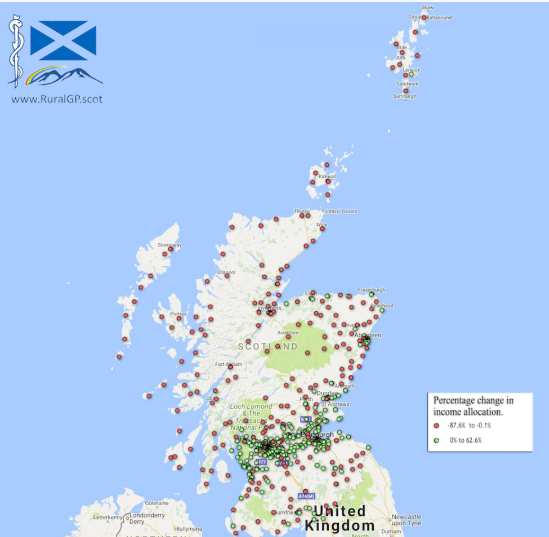

The second factor is less tangible than reliable information. It is trust. In our modern NHS, there are fewer GPs per head of population. At the same time, an older and less healthy population requires more health care. I could expand at length about the reasons for the reduction in whole-time equivalent GPs, but that is for another day. The upshot is that it has become harder to get an appointment with a GP and harder to see a GP that you have seen before. Continuity of care is disappearing, a loss to GPs and patients alike.

I polled a group of friends and relatives where they sought healthcare advice. The general approach seems to be to consider what issue to address, then to speak to friends and relatives first, perhaps supplemented by google. Only about half of these discussions led to a GP being involved at all, and any outcomes were further reviewed with relatives and friends. Clinically trained relatives, and those with the same condition, were the favoured sources of advice and discussion.

I asked these same friends and relatives about whether they usually saw the same GP, and whether they trusted their GPs. None of them could say who their GP was, or saw the same GP each time. Only half of them said they trusted their GP. I will quote one perspicacious reply:

‘ I trust them not to act maliciously, but I don’t trust them to think specifically about nuance or care beyond the superficial.’

How telling. The erosion of continuity of care has eroded trust and understanding, nuance and personalised medicine. Increasingly available and more complex information makes it harder to discriminate and evaluate the reliability of the information, how much weight to give it and whether it applies. Without trust from a wise navigator, where is realistic medicine? How do people without a clinically qualified relative cope? If General Practice has been reduced to a ‘painting by numbers’ service, how can personalised choices be considered?