I was very excited when I read about this study, about improving inpatient safety by systematically improving communication with patients and families during ward rounds. I could see immediately how this could be transferable to our own setting in the community hospital.

The entry in the paper BMJ is quite short and humble, and it is worth visiting the online version for more detail, and to see the short video clip introducing the key researchers, who describe the design and outline of the project.

https://www.bmj.com/content/363/bmj.k4764

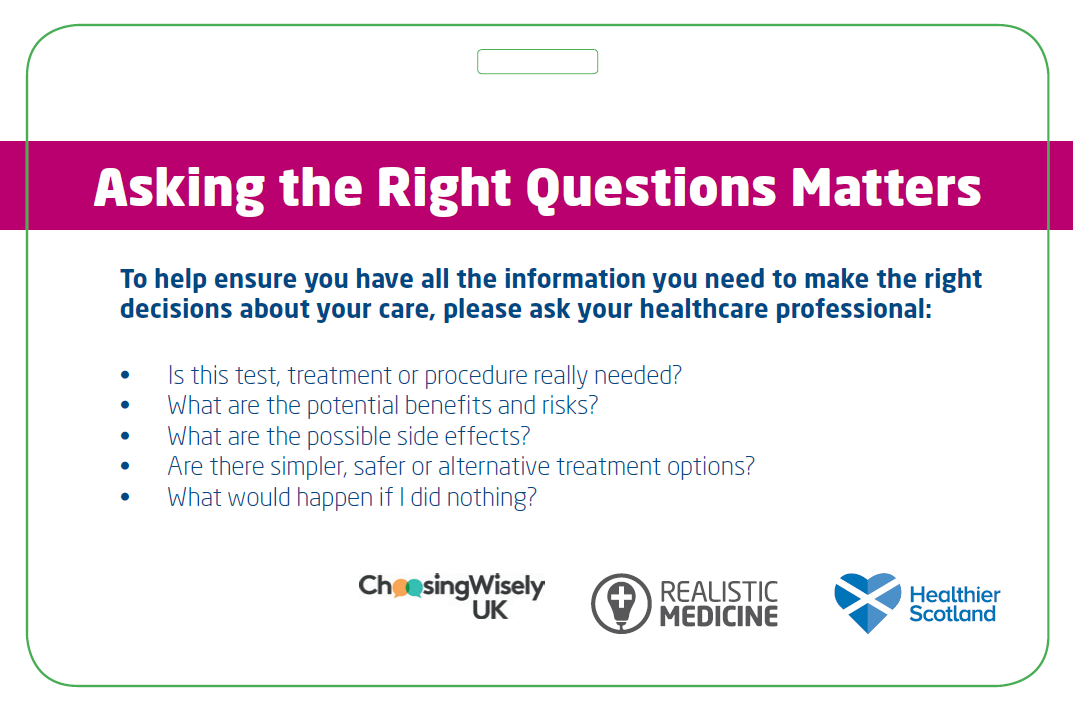

Structured ward rounds aren’t new, and neither is the concept of ‘no decision about me without me’. No-one would deny that families are an important part of the team providing care to patients. Using a structured communication tool has been embedded in our practice for many years. Teach-back is an excellent way of ensuring that the person receiving information has truly understood. The genius idea was to do all these things as a single process, and designing the intervention with service users.

The lead researchers are from the Children’s Hospital in Boston, Harvard Medical School, Mothers against Medical Error, and the Patient-Centred Outcomes Research Institute. They set out to introduce a method of improving communication with families. Their theory that this would improve outcomes was based on the observation that improving communication between clinicians improves safety, and that poor commmunication is a leading cause of adverse events.

The study group was made up of over 100 people, patients, nurses, family members, doctors, health literacy experts, researchers and medical educators. They co-produced the structured ward-round tool, to be used on ward rounds where the family is present. The communication tool is called I-PASS. They also produced a training package and a range of support tools including patient information leaflets.

A word about communication tools: We use SBAR locally, whereas I-PASS is the tool used in the study. It is designed to be used for structured communication with patients and families. It focuses more on the recommendations, and adds synthesis and teach-back as part of the communication tool.

I–Illness severity (family reports if child was better, worse, or same); nurse input solicited

P–Patient summary (brief summary of patient presentation, overnight events, plan)

A–Action list (to-dos for day)

S–Situation awareness and contingency planning (what family and staff should look out for and what might happen)

S–Synthesis by receiver (family reads back key points of plan for day, prompted by presenter, supported by others as needed)

The measures used were:

- Outcome measure: Looking at error rates, and harmful errors

- Outcome measure: Patient and family satisfaction

- Balancing measure: Length of ward round

- Balancing measure: Amount of teaching on ward round.

- Process measure: Communication processes on ward round.

Although overall error rates were unchanged, harmful medical errors decreased and Satisfaction scores rose and communication processes improved. There was no significant impact on ward round length or teaching on ward rounds.

My own experience over the years has been that I have shifted from asking family members to leave the room during rounds, to asking if they can stay. The conversations around progress and plans for care involve families and patients equally. Bringing in students adds a dimension of teaching, usually in patient-centred language, and it enriches the discussion. These conversations lead to patient-centred decisions, which are understood by relatives as well as the patients.

In the words of Helen Haskell, president of Mothers against Medical Error, one of the lead researchers, ‘It doesn’t just feel good, it can help improve the safety and quality of care – I would add, improve health literacy, agency and opportunity for realistic, patient centred care to be forefront of care planning. This study is a model of how families and care provides can co-produce an intervention to make care safer and better.’