What is the risk that this treatment will harm you? Is there a chance that a test will give a misleading result, leading to a misdiagnosis? What is the likelihood that your new diagnosis will have a good or bad outcome?

The practice of medicine is full of the management of risk, and communicating risk. There is a whole annual conference, called Risky Business, aimed at nurses, doctors and others, discussing how to assess and manage risk. One telling quote from a participating organisation, Cincinnati Children’s hospital: ‘We cannot compete on safety. We have a moral obligation to share anything we have learned which will help another…’ From the macro to the micro; as individual clinicians in the one-to-one consultation, we have an ethical duty to share what we know about risk, and to share it in a way that is easy to evaluate.

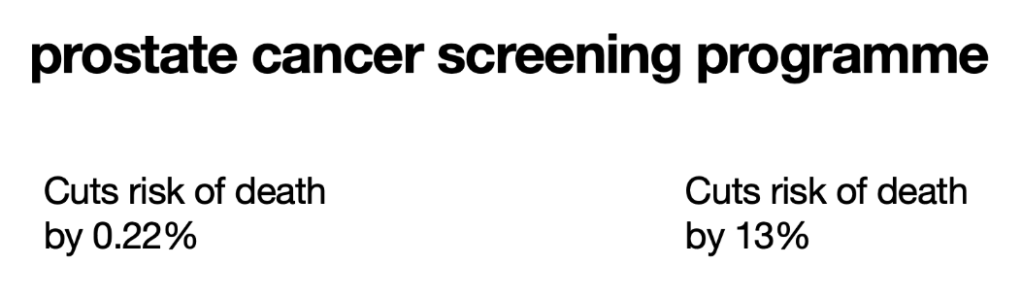

As humans, we are heavily influenced by the way that risk is presented. Relative risk or absolute risk? As a percentage, hazard or odds ratio? The figures can seem very persuasive and it is not always easy to understand what it means, especially at an individual level.

I’m a fan of Dr Margaret McCartney, a GP from Glasgow. She also has an academic role at St Andrew’s University, where she is the Director of the Centre for Evidence and Values in healthcare. She is interested in many things, including evidence based medicine, screening, risk, bias, and public communication about healthcare. What follows is her illustration on the communication of risk, focusing on a very topical issue; whether to screen for prostate cancer.

Which test would you choose? How would you feel if I told you this was the risk information from the same paper presented in two ways? After 23 years of follow-up, the risk of death from prostate cancer was 1.4% in the screened group and 1.6% in the unscreened group. That is about 0.2% reduction in absolute risk. 1.6 reduced by 13% is 1.4, so that is the relative risk. It is the second figure that has grabbed the headlines and the attention of politicians. As the patient and GP, it is the first figure that we should consider. The screening test also includes some harms, including over-diagnosis and over-treatment, with a very small reduction in risk.

Effective communication of risk in general practice is essential not only for patient understanding but also for fostering trust and shared decision-making. Building on the foundational importance of risk communication, practitioners must tailor their approach to each patient’s level of health literacy and cultural background. This involves using clear, non-technical language, visual aids, and analogies that resonate with individual experiences, while also being mindful of the emotional impact that risk information may have.

Furthermore, engaging patients in open dialogue allows them to express concerns, ask questions, and clarify misunderstandings, which ultimately supports informed consent and adherence to management plans. By continually refining communication strategies and adapting to the evolving needs of patients, general practitioners play a pivotal role in demystifying medical risks and facilitating effective healthcare outcomes.

HOW TO COMMUNICATE RISK, BENEFIT AND HARM:

- Use absolute risk rather than relative risk. In the PSA article, the absolute risk reduction is from 1.6% to 1.4%

- What are the risks of a disease without treatment.

- What are the absolute risks of harm of any particular treatment?

- What is the burden of treatment? How will the treatment (or lack of it) affect quality of life, and for how long?

Using risk alone to guide decision making is insufficient; in the mix is the needs of you the patient, your goals, what is important and what is achievable. Few of us can remember all of the known risks of every treatment; using patient decision aids helps to support communication of risk. NICE, NHS England, Cochrane, the University of Ottawa all have decision aids of varying quality. Ask your doctor where to find the best decision support for the condition you are discussing.